Student Loans Explained

On average, a UK graduate leaves university with £45,000 of debt. But that isn't necessarily how much they repay. How much university costs in total is completely delinked from what you end up paying. You can pay back anywhere between £0 and £140,000.

Navigating our student loans can feel daunting and confusing. The price tag of university seems only to increase each year, leaving many prospective students with an overwhelming feeling that they will be burdened by debt for the rest of their lives. Post-graduation isn't any better. Many of us feel alarmed when we first log into our student loan accounts and face a spiralling balance.

In this article, we'll explore the practical financial impact a student loan could have on you.

By the end of this read, we aim to have you equipped with all the information you need to understand how student loans work so that you can go away and make an informed decision when it comes to deciding to take out a student loan.

If you live in the UK and wish to study at university, you'll most likely have taken out, or need to take out a student loan.

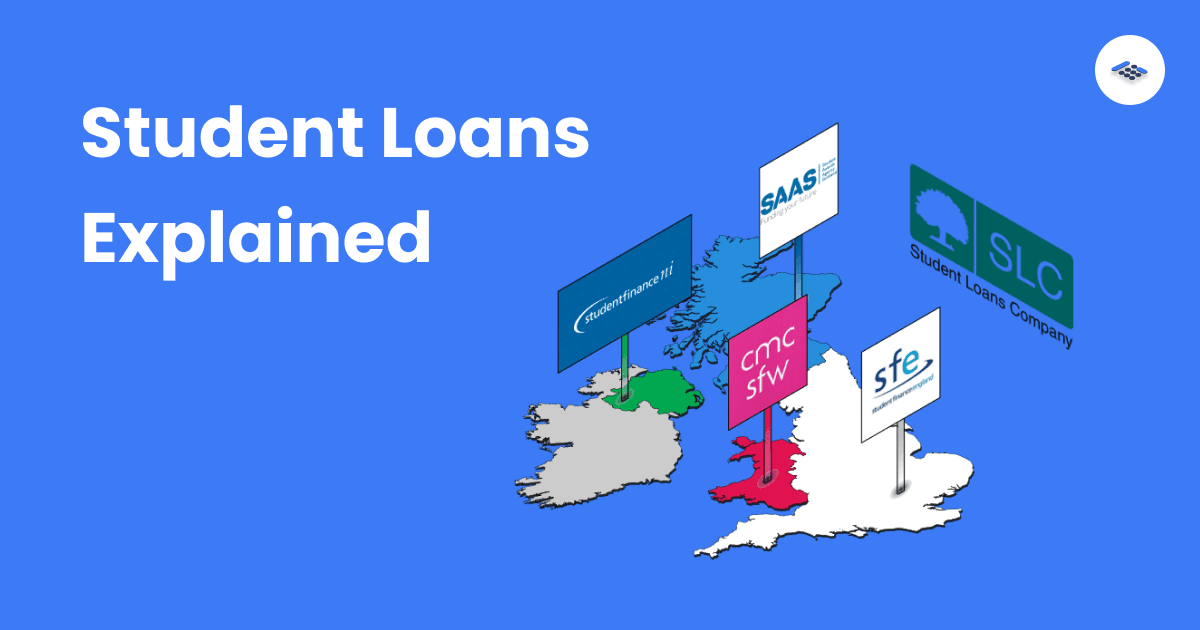

Depending on where you're from in the UK, you will apply for a student loan through:

- Student Finance England

- Student Finance Wales

- Student Awards Agency Scotland

- Student Finance Northern Ireland

These organisations work with the Student Loans Company (SLC) to deal with your application and loan allocation. Then, when you graduate and are liable to start repaying, SLC deals with your loan repayments.

There are two main types of student loans in the UK; Mortgage Style (MS) and Income Contingent Repayment (ICR). This article only covers the current ICR loan type (which is from 1998 onward).

Every ICR loan is on one of the following repayment plans:

- Plan 1 (before Sept 2012 or Northern Ireland only)

- Plan 2 (Sept 2012 - July 2023)

- Plan 3 (Postgraduate loans)

- Plan 4 (Scotland only)

- Plan 5 (Aug 2023 onward)

Think of a repayment plan as a pot of money that you owe, with some conditions. You need to pay back:

- Tuition fee loans

- Maintenance loans

- Accrued interest

When you start repaying your loan, how much you repay, for how long you repay and how much interest is applied each month to your loan depends on the repayment plan you are on.

The latest for each of the above is:

| Plan type | Repayment threshold | Interest rate | Max years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plan 1 | £24,990 | 4.30% | 25 |

| Plan 2 | £27,295 | 4.30% - 7.30% | 30 |

| Plan 4 | £32,745 | 4.30% | 30 |

| Plan 5 | £25,000 | 4.30% | 40 |

| Postgraduate | £21,000 | 7.30% | 30 |

You don't get to choose the repayment plan you are on; you're automatically put on one depending on what kind of degree you are studying and where you're studying it (the letters you get about your student loan should specify what plan you are on). You could be on different plans if you have more than one loan.

To determine which repayment plan you might be on, check out the government website.

So how much does it really cost to go to university in the UK?

You might say around £9,000 a year, or £50,000 for the degree. This is somewhat correct, as that's the price tag we often see. The real answer is that nobody knows how much it will cost you in particular. It's going to be different for everyone.

How much university costs in total is completely delinked from what you actually pay. This is extremely important to understand. The actual cost of university for you will range somewhere between £0 and £140,000.

This is because the key factor determining how much you pay is based on your income and not on how much you borrowed; you repay 9% (6% for Postgraduate loans) of any income above the 'repayment threshold' towards your student loan. Each repayment plan mentioned above has its repayment threshold, which changes yearly.

The latest thresholds are:

| Plan type | Repayment threshold |

|---|---|

| Plan 1 | £24,990 |

| Plan 2 | £27,295 |

| Plan 4 | £32,745 |

| Plan 5 | £25,000 |

| Postgraduate | £21,000 |

You'll repay:

- 9% of any income over the repayment threshold towards your Plan 1, 2, 4 or 5 loan

- 6% of any income over the repayment threshold towards your Postgraduate loan

As an example, let's take the latest Plan 2 repayment threshold of £27,295 and let's suppose you earn £37,000.

£9,705 is the amount of your income over the repayment threshold.

Of that £9,705, 9% of it will go towards paying off your Plan 2 loan which amounts to £873.

That means you pay roughly £73 per month towards your student loan in that year.

Consider the current ICR student loan system as a no-win no-fee; if you earn a lot (you've "won"), you repay a lot more. If you don't earn a lot, you repay less, or potentially even nothing. Unfortunately, as we'll explore in the next section, this isn't exactly true.

Hopefully, you can start to see how this works and why how much university costs in total is completely delinked from what you actually end up paying.

When many people first look at their SLC statement and see something like £45,000 of debt with £10,000 of interest added (and interest continuing to be added), they panic and immediately feel like they have this crippling debt looming over their head. While technically speaking, you are indeed in debt, and this debt continues to accrue interest, the practical impact of this debt in reality will be different for everybody.

In this section, we'll further explore the single most important factor in determining how much university will cost you; your income. Remember that the price tag quoted to you (including any accruing interest) and what you end up paying is delinked because your income determines all repayments - you pay 9% (6% for Postgraduate loans) of your income above a repayment plan's threshold towards your debt. The more you earn, the more you pay towards your debt.

With this in mind, let's start by looking at who clears their debt and who doesn't.

First, we'll split graduates into the following five different lifetime income groups to illustrate how different levels of lifetime income can impact the real cost of a student loan and the scale of repayments:

Lowest lifetime earners (1-9th percentiles of UK graduate earners)

Individuals who earn less than 90% of other loan borrowers over their lifetime. An income which is under the threshold for most of their working life.

Low lifetime earners (10-39th percentiles of UK graduate earners)

Individuals who earn more than the lowest earners but less than the top 60% of loan borrowers. An income around or just over the threshold for most of their working life.

Middle lifetime earners (40-69th percentiles of UK graduate earners)

Individuals who earn more than the low earners, but less than the top 30% of loan borrowers. An income which is a good chunk above the threshold and with above inflation pay rises for most of their working life.

Higher lifetime earners (70-89th percentiles of UK graduate earners)

Individuals who earn more than all except the top 10% of loan borrowers. An income which is a big chunk above the threshold and with above inflation pay rises and/or decently sized pay rises for most of their working life.

Highest lifetime earners (90-99th percentiles of UK graduate earners)

Individuals who have lifetime earnings in the top 10% of all loan borrowers. An income which is a huge chunk above the threshold and with far above inflation pay rises and/or big pay rises for most of their working life.

Next, let's pick eleven percentiles which make up all the lifetime groups and give each of them the same £50,000 Plan 2 loan, and map out how much they all pay from the first April after graduation until their loan is either written or paid off:

You can see the relationship between how much a graduate has paid in total by the end of the repayment period, and how much they earn. The more they earn, the more they pay, although this starts to go back down again as they enter higher-income groups. It starts to go back down again because the highest of earners pay off their loans much quicker; there is less time for interest to accrue, and the monthly interest becomes smaller much quicker as their debt reduces quicker.

This graph also closely aligns with the government's predictions of who pays off their loan in full and who doesn't. The government predicts that approximately 25% of Plan 2 graduates are expected to pay off their loans in full, including interest, whilst 75% are expected to have their loans written off.

Keep in mind that this graph is more of an art than a science; you might be a low earner for five years and then a high earner for the 25 years after that, so that will map out differently. Or if you took out a smaller loan, this graph will look different for you (the peak will shift to the left and down). If interest reduces or increases, the graph will also look very different. There'll be unique graphs for each repayment plan and debt amount; if you have more than one loan, that'll look different, too.

The main point of the graph is to illustrate the cost of university for different graduate lifetime income groups so that you can start to get a better idea of how much you will pay depending on which lifetime income group(s) you will most likely fall into.

The decision to pay off a student loan has undoubtedly crossed every graduate's mind. Nobody likes being in debt.

Before you overpay anything, however, it is important to consider and remember the following: the cost of university is completely delinked from how much you will pay because you pay back an amount based on your income.

We saw that not everyone will end up paying their loan in full.

The way we'll explore the overpayment question is to split graduates into two categories: those who will pay their loans off in full and those who will have them written off.

The advice given to graduates who will pay their loans off in full (typically high earners) will be different to what is going to be said to graduates who will have their debts written off.

Advice to High Earners

If you are most likely part of the high lifetime income group, then overpaying can be a sensible thing to do as you might significantly reduce how much interest you pay back. If you're not sure what lifetime income group you're going to be a part of, always use the following to determine whether an overpayment is a good idea; if your overpayments will make a significant difference in how much you pay back in total, then it might be worth making them, keeping in mind that:

- You have to throw a large lump sum at your debt or make consistent monthly payments, or else it's money wasted

- There is an opportunity cost to using that money for paying this particular type of loan off; what if investing that money yields you more money than the money you saved by reducing how much interest you end up paying? What if you suddenly need access to that money and, as a result of overpaying, now have to borrow money from elsewhere at higher interest rates? This money could go towards a house deposit, starting a business, an emergency fund, etc. The decision to overpay has to be thought through and generally isn't a good idea for most graduates

- What if you were making consistent monthly overpayments, but a sudden change in living costs means you can no longer keep them up? if those overpayments didn't make a big enough dent in your debt, then it was all money wasted.

This Feels Like Guesswork

Trying to predict how much you will earn over the next few decades and thus how much you should voluntarily overpay can feel like it will be at best a guess since there are so many unknowns. Making sensible assumptions about your earnings is very worthwhile because if you're in the camp where your loan will cost you £140,000, you could make significant savings. What is most important is that you have to be pragmatic about this. If you know you will likely be a high earner for most of your working life; you can sensibly reduce how much interest you are paying by overpaying. But as mentioned, those extra payments should be money you're happy to part with, can't be put to better use such as an investment, and must be accompanied by a well-thought-out strategy.

If you start overpaying and one year in decide to stop but have already overpaid by £1,000, that's £1,000 thrown down the drain. The bottom line is: don't commit to overpaying if it will not significantly reduce how much you pay back in total, and there aren't any better investments to put your money towards. The content on this website is a tool you can use to see how different factors affect the scale of your loan repayments. Your life will diverge from these predictions, and everything you see is but a guide.

To better illustrate the money wasted point, suppose you graduate with £50,000 worth of debt, and at the end of the repayment period, you have repaid a total of £29,000, based on your income during those 30 years. The remaining £21,000 + accrued interest is written off.

If you had put £10,000 towards that £50,000 at the very start, and your income during those same 30 years is identical, the remaining £11,000 debt would still be written off. In both cases, you would have never paid your loan off in full, so that £10,000 you paid at the start was wasted.

Even if just £1 of debt remains and is written off at the end of your repayment period, any overpayment would have been money wasted.

I'm Committed to Overpaying, How Much Should I Overpay By?

You've made your mind up and done your due diligence, and you feel voluntary overpayment is right. Make sure it is. This article does not constitute financial advice, and it's always a good idea to seek out a financial advisor.

Okay, so you're committed. What should your overpayment strategy be?

First, if you are a high earner and your mandatory monthly payments are much higher than the accruing interest, you don't have to necessarily add any overpayment on top, as you'll be on track to pay off your loan. Overpaying will speed up this process and save you even more money.

Otherwise, the higher the debt, the more interest accumulates, and you would want to get the interest under control. The quickest way is to throw a sizeable lump sum at your loan. If you do this, less interest will accrue because your debt has now been reduced. A different strategy that takes a little longer to achieve the same outcome is regular and large monthly overpayments.

When your debt is much lower, much less interest will accrue (especially when the interest rate is low), so you can be less aggressive with your overpayments as the interest is now manageable.

Remember that circumstances can change anytime and that overpaying isn't a financially sensible option for most graduates. Make sure you think this through properly, that your overpayments will significantly affect how much you end up paying back, and that there isn't a better investment to put this money towards (there usually is).

Advice to Everyone Else

Most graduates will probably not think about overpaying as they don't earn enough to make a significant difference with overpayments. If you find yourself in this category, you can treat loan repayments as an extra 9% of tax for the rest of your working life.

If we take a non-graduate and a graduate and pay them identical salaries every year for the next few decades, they'd pay the following tax rates for each tax bracket:

Whilst most graduates don't have to worry about a £60,000 debt looming over their head (some won't pay back a single penny), no one is saying the extra 9% in taxes is cheap either. Before even considering taking out a loan, consider whether university is worth it or not or if your time is better spent doing an apprenticeship, a part-time degree, starting your own business, or doing something else altogether.

All or Nothing

If you are set to take out a full student loan, remember that it doesn't have to be an all-or-nothing choice. You don't have to choose between taking out any loan or a full loan. You could work during college and university, spend a year in industry or try to get a summer internship to cover part of the living and university costs so that you only need to take out a smaller loan. But again, very crucially, if you decided to work part-time before or during university and over summer breaks to put money towards your student loan and living costs, there's an opportunity cost associated with that. Could that money have been better spent elsewhere? Only you can answer that question.

One thing we haven't quite touched on in detail yet is interest rates. We've all seen headlines talking about student loan interest rates reaching as high as 12% (thankfully that didn't happen due to the government stepping in).

Touching back on this article's start, we know there are different repayment plans. Each of these repayment plans has its own interest rate. Interest starts to accrue the moment you take a loan out. Interest accrues every day and is added to your total debt at the end of every month.

For all plans except Plan 2, the interest rate should be set to RPI, the retail price index, which measures inflation. Inflation generally means the price of things increasing; how much you pay for something this year, will likely cost a little bit extra next year. For example, milk might cost £1.00 per litre in 2022, and in 2023 it could cost around £1.10 per litre, depending on the inflation rate. The Bank of England shows an average inflation rate of 2.1% for the years 2000-2018. As of September 2022, inflation is around 10% according to the Bank of England.

Much like the loan amount you take out and what you actually pay back is completely delinked, the interest added is not the same as the interest you pay. Why? Because the tuition and maintenance loan you can take out as well as the interest added on top, are all part of the same repayment plan pot. If you take out a £50,000 loan and £20,000 of interest accumulates, that's £70,000 in the same pot, and it's only your income which determines how much of it you pay back, as we illustrated in the previous sections of this article.

Going back to RPI and how it relates to student loans, if the interest rate on a student loan is set exactly to inflation, then in essence this means that there is no real cost to your student loan, because if every year interest is added to your debt at the rate of inflation, then every year your debt is "worth" the same.

Because of inflation, the cost of your loan over 30 years will be less in real terms.

Currently, the Plan 2 interest rate is an exception to the RPI rule. Its interest rate is set to RPI + up to 3%. The up to 3% depends on your income. It is on a sliding scale between £27,295 and £49,130 in 2022. If you earn less than £27,295, 0% is added to your interest rate. If you earn £49,130 or more, 3% is added to your interest rate. In between, some % amount between 0-3 is calculated. It is set to 3% whilst you are studying. All other plans have an interest rate of just RPI. The actual interest rates and repayment thresholds can be found on the government website. There are different pages for the different plans. The calculator on this website also uses those figures, and you can view them all in one place on the data page.

You've borrowed some money to study at university and have graduated. This means you're now liable to start repaying your student loans. Repayments start from the April after you leave university (the Statutory Repayment Due Date), regardless of whether you left due to dropping out of university or graduating.

For most of us, repayments are automatically taken through PAYE, every time we get our wage and it is above the repayment threshold.

The latest thresholds are:

| Plan type | Repayment threshold |

|---|---|

| Plan 1 | £24,990 |

| Plan 2 | £27,295 |

| Plan 4 | £32,745 |

| Plan 5 | £25,000 |

| Postgraduate | £21,000 |

Repayments continue until either the total loan (plus added interest) is paid off, or after 25 to 40 years, depending on the repayment plan, when any remaining debt is written off.

Multiple Jobs

If you have more than one job, repayments will be from the jobs where you earn over the threshold and not your combined income.

Multiple Loans

If you have more than one loan you still only make one repayment.

Postgraduate loan repayments are paid concurrently with Plan 1, Plan 2 and Plan 4 loan repayments.

This means if you have a salary above the Postgraduate repayment threshold, you will pay 6% of the difference towards your Postgraduate loan. Let's call this repayment A.

If that same salary is also above one of the other plan (Plan 1, Plan 2 or Plan 4) repayment thresholds, you will pay 9% of the difference towards one of those other plans. Let's call this repayment B.

Repayments A and B happen concurrently.

If you have more than one non-Postgraduate loan, repayment B will be allocated against the different non-Postgraduate loans depending on how much you earn and the repayment thresholds. Repayments are calculated between threshold amounts and allocated to each of those slices.

To illustrate how this works, suppose someone has a Postgraduate, Plan 1, Plan 2 and Plan 4 loan (not realistic, but to make the point). And let's suppose they earn £45,000. This is what repayments would look like:

Repayment for Postgraduate loan

(Income) - (Postgraduate threshold) = Amount over threshold

£45,000 - £21,000 = £24,000

6% of £24,000 = £1,440 paid for the year.

Repayment for non-Postgraduate loans

For their non-Postgraduate loans, repayment will be spread across each of them by calculating the difference between each threshold (after they are put in order of largest to smallest) and paying 9% of each of those differences (the difference for the first plan on this list is calculated against the income). The ordered list would look like this:

- Income - £45,000

- Plan 4 - £32,745

- Plan 2 - £27,295

- Plan 5 - £25,000

- Plan 1 - £24,990

And this is what repayments look like for each plan:

Replayment for Plan 4

(Income) - (Plan 4 threshold) = Amount over threshold

£45,000 - £32,745 = £12,255

9% of £12,255 = £1,103 paid for the year.

Replayment for Plan 2

(Plan 4 threshold) - (Plan 2 threshold) = Amount over threshold

£32,745 - £27,295 = £5,450

9% of £5,450 = £491 paid for the year.

Replayment for Plan 5

(Plan 2 threshold) - (Plan 5 threshold) = Amount over threshold

£27,295 - £25,000 = £2,295

9% of £2,295 = £207 paid for the year.

Replayment for Plan 1

(Plan 5 threshold) - (Plan 1 threshold) = Amount over threshold

£25,000 - £24,990 = £10

9% of £10 = £1 paid for the year.

Total repayment

- Postgraduate loan - £1,440

- Non-postgraduate loans - £1,801

Retrospective Changes

The government can make retrospective changes to the rules you agreed to when you took your loan out. Interest rates, repayment thresholds, repayment rates and repayment periods can all change. The government did this once in November 2015 when they froze the repayment threshold for Plan 2 loans, whereas they should have gone up with average UK earnings.

It could happen again, and you should be aware of this risk.

Augar Report

A new plan is coming in September 2023 - Plan 5. You can read more about it here.

If You Pass Away

The debt is wiped if you die, and no one inherits it. If you become permanently disabled and that makes you unfit for work it is also wiped.

Got a Loan but Didn't Graduate?

Not graduating does not wipe out your loans. You still have a pot of money in one of the repayment plans which you owe SLC.